The staging of Cymbeline at this year’s Bard on the Beach squares out the themes of “daughters and redemption”. While A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Cymbeline center around defiant daughters, The Tempest and Equivocation touch on restoring a rightful legacy to a daughter.

Unparalleled performances and harmony of motifs make the 25th anniversary productions of Bard one of this summer’s highlights.

Cymbeline’s plot is excessively complex, likely because there are so many! One of Shakespeare’s final plays, Cymbeline falls into the mezzo category of a tragicomedy – a tragedy with a happy ending. When King Cymbeline wrongfully banishes faithful nobleman Belarius from his court, Belarius retaliates by kidnapping the king’s two young princes; Cymbeline has long given them up for dead.

Now Imogen, the king’s virtuous daughter, has chosen to marry a commoner, Posthumus, against Cymbeline’s wishes. The enraged king imposes banishment on the devoted but gullible youth and the wheels of fate turn once again. This time they will spiral out of control, culminating in a British-Roman war and reunions begotten through outlandish means.

[In foreground: Anton Lipovetsky, Bob Frazer]

Deception is a prevalent theme for all characters in this story. The seemingly loving Queen has murderous intentions; the wily Italian, Iachimo, wins his bet through underhanded trickery; even the dutiful doctor, Cornelius, is shrewd enough to substitute poisons. Duality of intentions are complimented with physical duality of identities.

The queen’s loathsome son, Cloten, dresses up as Posthumus; Imogen disguises herself as a male page; Cymbeline’s royal sons live as simple rustics. At one time or another, most of the 13+ characters in the play masquerade as someone else.

Weave in five parallel plot lines, three locales (Britain, Wales, Italy), the final convergence of revelations, and Cymbeline feels both haphazard and convoluted.

Some scholars have proposed that Shakespeare liberally borrowed from Boccaccio’s Decameron while others suggest he collaborated with a lesser playwright on this pastiche. Cymbeline’s heavy on plot and light on style, snatching at highlights of Shakespearean masterpieces, yet only succeeding at a patchwork finale. A savvy choice by director Anita Rochon is to accentuate the comedic components so the tragic elements are easier to digest.

Rochon has also made a keen substitution to omit staging the influx of supernatural elements while a sleeping Posthumous dreams of his forlorn love. While rich imagery and wordplay are littered throughout the play, much of these gems can be lost while the observer is trying to keep up with the story lines. Listen closely for one of the most exquisite funeral ballads in Shakespeare’s repertoire.

[L to R: Rachel Cairns; Gerry Mackay, Shawn Macdonald]

None of the characters – except Imogen and Iachimo – are fully developed enough to garner affinity with the audience. Rachel Cairns imparts an ambrosial portrayal of the aggrieved princess, both in her crisp dialogue and minute non-verbal body language. However, at times, it was difficult to hear her speech as her delicate voice is not as orotund as the male players.

Bob Frazer’s crafty Iachimo is infinitely entertaining to watch. On first appearance, he is nothing more than an arrogant, unethical cad. Frazer, through his impassioned delivery and deliberate comical touches, salvages the character from total villainy.

[L to R: Bob Frazer, Anousha Alamian]

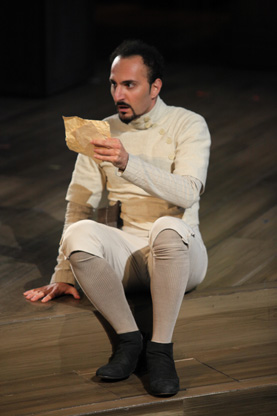

The remaining plethora of characters are played by only six actors, who must convincingly adopt two to four personalities each. An infallible example, Anton Lipovetsky endures a cardio workout trampling around the stage as Posthumus, Posthumus-in-disguise, Cloten, Cloten in disguise, Arviragus and Cadwal. The blandness of the unworthy Posthumus is contrasted by the thoroughly absurd villainy of the clumsy Cloten.

[Anton Lipovetsky, Shawn Macdonald, Benjamin Elliott]

His waggish portrayal mirrors that of the hateful Joffrey from the popular Game of Thrones HBO series, yet Lipovetsky also manages to flourishingly transform into the wide-eyed rustic Cadwal. Similarly, Shawn Macdonald deliciously plays the deceitful Queen, heartily embracing the Shakespearean tradition of males playing females.

From a slight raise of the eyebrow to the stiff poise of fingers, Macdonald imparts gleeful wickedness. Further merriment ensues when Macdonald later appears as the doting and fatherly Morgan (Belarius in disguise).

Mara Gottler’s practical costumes are meant to visually aid in the differentiation of various identities. At first glance, the fencing-inspired livery, although clean and sleek, appeared underwhelming. The attire for the Britons resembled reams of curtains; the Welsh rustics wore mangled versions of cumbrous burlap. Soon however, Gottler’s ingenuity is exposed by a clever crafting of diverse fabrics, textures, and colours that define each venue while allowing for hasty costume swaps.

Although the staging of Cymbeline with only a few actors is not a new concept, the practice imports yet another layer of distraction in an already complicated play. Happily, Pam Johnson’s minimalistic yet warm and uncluttered scenic design functions effectively for the set. Lighting designer Alan Brodie nimbly toys with lights and shadows, projecting castle turrets, a twinkling sky, and silhouettes of a blustering army.

[L to R: Shawn Macdonald, Anton Lipovetsky, Benjamin Elliot; Rachel Cairns, Bob Frazer]

Unreserved accolades are offered to the superbly talented cast (Anousha Alamian, Benjamin Elliott, Bob Frazer, Anton Lipovetsky, Shawn Macdonald, Gerry Mackay) who also play a variety of instruments in the background (using original music composed by Benjamin Elliot). Their skills, united with the immeasurably adept stage management team (Joanne P.B. Smith, Samara Van Nostrand, Jennifer Stewart), provide a major contribution to the success of the production.

Rochon dubbed the mounting of Cymbeline a “Herculean” task. The execution of the final pivotal scene of the play is much like slaying the Lernaean Hydra – as one head is severed, another two sprouts in its place. A near impossibility to have all the characters on stage simultaneously, the actors strip off and don their paltry costumes with abandon. They do lickety-split shifting from role to role and spawn an ending that is both hilarious and revealing. Amidst a chortling audience and dripping in their snug apparel, their ability to stay in character and bring the play to a successful conclusion is genuinely commendable.

Contrasting and opposite personalities are embraced by the players in Cymbeline. Lipovetsky is both the respectable Posthumus and the vile Cloten; Frazer is the unscrupulous Iachimo and the honourable Caius Lucius; Elliott is the stiff Cornelius and an immodest Frenchman; Macdonald is the treacherous Queen and an affectionate Belarius. These disparities highlight the inconstancies of true human nature and how life is stranger than fiction.

Although the play is a swirl of improbable happenstances and, as Rochon says, “situations that dare us not to believe”, we as individuals can choose to believe. Believe in the magic of this ensemble.

Cymbeline plays Tuesdays to Sunday until September 17. Photos by David Blue.